(1) John Ford — In the 1970s, long after the death of D. W. Griffith, many of the best film directors were asked who among them was the greatest living director. According to Kurosawa, Welles, Renoir, Fellini, and many of the others, the answer was John Ford. Consider the movies he made over just a three year period: Stagecoach (1939), Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Long Voyage Home (1940), and How Green Was My Valley (1941).

Some might dismiss Ford’s films, especially the later lesser films, as being overly sentimental. In an age of ironic and often brutal themes, you have to approach Ford on his own terms. Once you clue into the subtlety and insight of his storytelling, and the fact that his films tend to merge together into one massive narrative, you’ll find yourself confronted with a body of work that stands unequaled in film and with few equals anywhere else.

Not all Ford films are great films. To survive creatively within the studio system, he agreed to direct films he didn’t care about in order to direct films he did care about. Fortunately, for every Mary of Scotland (1936) and Wee Willie Winkie (1937), you’ll find a much-more personal The Informer (1935) and The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936).

Be sure to see The Informer (1935), The Prisoner of Shark Island (1936), Stagecoach (1939), Young Mr. Lincoln (1939), The Grapes of Wrath (1940), The Long Voyage Home (1940), How Green Was My Valley (1941), They Were Expendable (1945), My Darling Clementine (1946), Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), Wagonmaster (1950), The Quiet Man (1952), The Searchers (1956), and The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962).

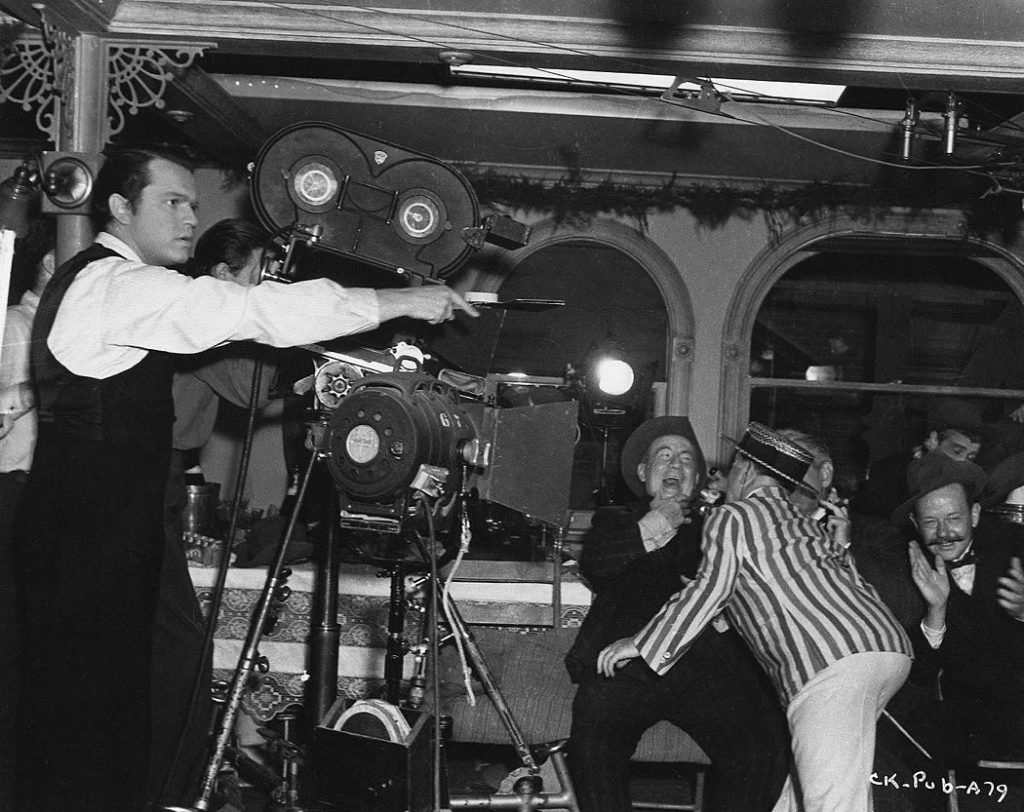

(2) Orson Welles — Only one of the films Welles directed was completed as he intended. That film was Citizen Kane. The other films were altered by the studios or compromised from lack of funds. That doesn’t mean that his only great film is Kane — far from it. Even with the sudden and out-of-place ending, and unfortunate edits throughout, The Magnificent Ambersons is a remarkable and innovative film. In many ways, it’s even better than Kane. Touch of Evil was so forward looking, we’re still trying to catch up with it. Even the no-frills The Immortal Story and the illusive F for Fake are far more rewarding to watch than you might assume at first glance.

Be sure to see Citizen Kane (1941), The Magnificent Ambersons (1942), Lady from Shanghai (1948), Macbeth (1948), Touch of Evil (1958), Chimes at Midnight [a.k.a. Falstaff] (1967), The Immortal Story (1968), and F for Fake (1975).

(3) Akira Kurosawa — Just as John Ford is often written off as a mere director of westerns, Kurosawa is often dismissed as a mere director of samurai films. Yet his films set in contemporary times are just as good — taken as a group — as his samurai films. His post-war urban crime dramas show a knack for rich characters and flowing narrative that would serve him later in such outstanding films as Ikiru, Red Beard, and Dersu Uzala. His final film (Madadayo), generally underrated, is remarkably polished in its simplicity and assured storytelling. Like Buñuel (and unlike Griffith and Ford), Kurosawa was able to stay fresh and interesting as an aging director, even into his 70s.

Be sure to see Stray Dog (1949), Rashomon (1950), Ikiru (1952), Seven Samurai (1954), Throne of Blood (1957), The Lower Depths (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958), Yojimbo (1961), High and Low (1963), Red Beard (1965), Dersu Uzala (1974), Kagemusha (1980), Ran (1985), and Madadayo (1993).

(4) Jean Renoir — Like Ford, Renoir is a people person. Narrative and film technique serve to reveal what they can about the characters. Also like Ford, Renoir is an optimist. Neither director dismisses the power of personal corruption, but both are more concerned with the rich rewards of human relationships and how they play out against dramatic circumstances. Renoir’s best films play like the best novels with rich characters that are instantly recognizable and likable, despite their obvious flaws. If you prefer films that offer deep insights into the human condition, Renoir’s films (along with Ford’s films) are a good place to start. In case you’re wondering, Jean Renoir is the son of the famous Impressionist painter, August Renoir.

Be sure to see Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932), Toni (1934), The Crime of Monsieur Lange (1935), La Bête Humaine (1938), Grand Illusion (1938), Rules of the Game (1939), The Southerner (1945), Diary of a Chambermaid (1946), The River (1951), French Cancan (1956), and The Little Theater of Jean Renoir (1969).

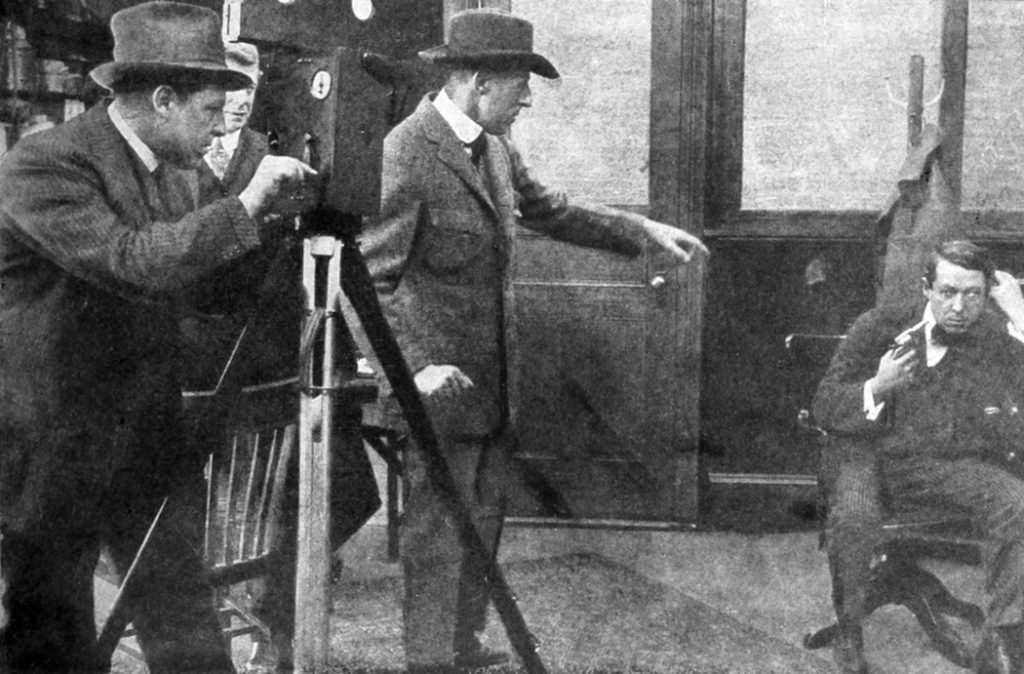

(5) D. W. Griffith — Yes, Birth of a Nation is a racially naive and historically destructive film. Does that mean we should reject everything Griffith accomplished? Probably not. Many of Griffith’s earliest films survive because the Library of Congress required film production companies to submit paper prints to protect their copyrights. Converting these paper prints back into film prints, we can see Griffith experiment with a wide range of photographic and narrative techniques, as he invents (along with others) the film vocabulary we use today.

Be sure to see Birth of Nation (1915), Intolerance (1916), Hearts of the World (1918), Broken Blossoms (1919), True Heart Suzie (1919), Way Down East (1920), Dream Street (1921), and Orphans of the Storm (1922).

(6) Sergei Eisenstein — Be sure to see Strike! (1924), Battleship Potemkin (1925), October [a.k.a. Ten Days That Shook the World] (1927), Alexander Nevsky (1938), Ivan the Terrible, Part 1 (1942, released 1945), and Ivan the Terrible, Part 2 (1945, released 1958).

(7) F. W. Murnau — Be sure to see Nosferatu (1922), The Last Laugh (1924), Faust (1926), Sunrise (1927), City Girl (1930), and Tabu [directed with Robert Flaherty] (1931)

(8) Abel Gance— The most satisfy film theater experience I ever had was attending Gance’s Napoleon at Radio City Music Hall with a live orchestra. Be sure to see J’accuse (1919), La Roue (1922), Napoleon (1927), Lucréce Borgia (1935), Un Grand Amour de Beethoven (1937), and J’accuse (1938).

(9) Alfred Hitchcock — Be sure to see The Man Who Knew Too Much (1935), The 39 Steps (1935), Sabotage (1937), The Lady Vanishes (1938), Rebecca (1940), Foreign Correspondent (1940), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), Notorious (1946), Strangers on a Train (1951), Rear Window (1954), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), Psycho (1960), The Birds (1963), and Frenzy (1972).

(10) Charles Chaplin — Be sure to see The Pawnshop (1916), The Rink (1916), Easy Street (1917), The Immigrant (1917), A Dog’s Life (1918), Shoulder Arms (1918), Sunnyside (1919), The Kid (1920), The Pilgrim (1923), The Gold Rush (1925), The Circus (1928), City Lights (1931), Modern Times (1936), and The Great Dictator (1940).

(11) Buster Keaton — Be sure to see One Week (1920), Cops (1922), The Electric House (1922), Balloonatics (1923), Our Hospitality (1923), Sherlock Jr. (1924), The Navigator (1924), Seven Chances (1925), Go West (1925), The General (1926), College (1927), and Steamboat Bill Jr. (1927).

(12) Kenji Mizoguchi — Be sure to see Osaka Elegy (1936), Sisters of Gion (1936), The 47 Ronin [in two parts] (1941 & 1942), Utamaro and His Five Women (1946), My Love Has Been Burning (1949), Portrait of Madame Yuki (1950), The Life of Oharu (1952), Ugetsu (1953), Sansho the Bailiff (1954), Taira Clan Saga (1955), Princess Yang Kwei Fei (1955), and Street of Shame (1956).

(13) Howard Hawks — Be sure to see Scarface (1932), Twentieth Century (1934), Come and Get It [direction completed by William Wyler] (1936), Bringing Up Baby (1938), Only Angels Have Wings (1939), His Girl Friday (1940), Sergeant York (1941), Ball of Fire (1941), Air Force (1943), To Have and Have Not (1944), The Big Sleep (1946), Red River (1948), Monkey Business (1952), Gentlemen Prefer Blondes (1953), and Rio Bravo (1959).

(14) Federico Fellini — Be sure to see Variety Lights (1950), La Strada (1954), The Nights of Cabiria (1957), 8 ½ (1963), Juliet of the Spirits (1965), Fellini Satyricon (1969), The Clowns (1970), Fellini’s Roma (1972), Amarcord (1973), and And the Ship Sails On (1983).

(15) Ernst Lubitsch — Be sure to see The Student Prince (1927), The Love Parade (1929), The Smiling Lieutenant (1931), One Hour with You (1932), Trouble in Paradise (1932), Design for Living (1933), The Merry Widow (1934), Ninotchka (1939), The Shop Around the Corner (1940), To Be or Not to Be (1942), Heaven Can Wait (1943), and Cluny Brown (1946).

(16) Stanley Kubrick — Be sure to see The Killing (1956) , Paths of Glory (1957), Spartacus (1960), Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), A Clockwork Orange (1971), Barry Lyndon (1975), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Eyes Wide Shut (1999).

(17) Fritz Lang — Be sure to see Destiny (1921), Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler (1922), Die Nibelungen [a.k.a Siegfried and Kriemhild’s Revenge] (1924), Metropolis (1926), Spies (1928), Woman in the Moon (1929), M (1931), The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), Fury (1936), Man Hunt (1941), and The Big Heat (1953).

(18) Yasujiro Ozu — Be sure to see I Was Born, But… (1932), Story Of Floating Weeds (1934), There Was A Father (1942), Early Summer (1951), Tokyo Story (1953), Early Spring (1956), Equinox Flower (1958), Good Morning [a.k.a. Ohayo] (1959), Floating Weeds (1959), Late Autumn (1960), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962).

(19) Erich von Stroheim — Be sure to see Foolish Wives (1922), Greed (1925), The Merry Widow (1925), The Wedding March (1928), and Queen Kelly (1928).

(20) Carl Theodor Dreyer — Be sure to see Leaves from Satan’s Book (1919), Master of the House [a.k.a. Thou Shalt Honor Thy Wife] (1925), The Passion of Joan of Arc (1927), Vampyr (1931), Day of Wrath (1943), Ordet (1954), and Gertrud (1964).

(21) Josef von Sternberg — Be sure to see The Salvation Hunters (1925), Underworld (1927), Last Command (1928), Docks of New York (1928), The Blue Angel (1930), Shanghai Express (1932), The Scarlet Empress (1934), and The Devil is a Woman (1935).

(22) Luis Buñuel — Be sure to see Un Chien andalou [a.k.a. An Andalusian Dog] (1929), L’Age d’or [a.k.a. The Golden Age] (1930), Los Olvidados [a.k.a. The Young and the Damned] (1950), Nazarín (1958), Viridiana (1961), The Exterminating Angel (1962), Diary of a Chambermaid (1963), Simon of the Desert (1965), Belle de jour (1967), The Milky Way (1969), Tristana (1970), The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972), The Phantom of Liberty (1974), and That Obscure Object of Desire (1977).

(23) Dziga Vertov — Be sure to see Kino-Pravda (1922-1925), Stride, Soviet! (1926),A Sixth of the World (1926), The Eleventh (1928), Man with a Movie Camera (1929), Enthusiasm (1931), and Three Songs of Lenin (1934).

(24) Preston Sturges — Be sure to see The Great McGinty (1940), Christmas in July (1940), The Lady Eve (1941), Sullivan’s Travels (1941), The Palm Beach Story (1942), The Miracle of Morgan’s Creek (1944), and Hail the Conquering Hero (1944). Sturges began his career as a screenwriter. Among those films, be sure to see The Power and the Glory (1933), The Good Fairy (1935), Easy Living (1937), If I Were King (1938), and Remember the Night (1940).

(25) Martin Scorsese — Be sure to see Mean Streets (1973), Taxi Driver (1976), New York, New York (1977), The Last Waltz (1978), Raging Bull (1980), The King of Comedy (1983), After Hours (1985), The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), GoodFellas (1990), Casino (1995), Kundun (1997), Gangs of New York (2003), The Departed (2006), Shutter Island (2012), and Hugo (2011).