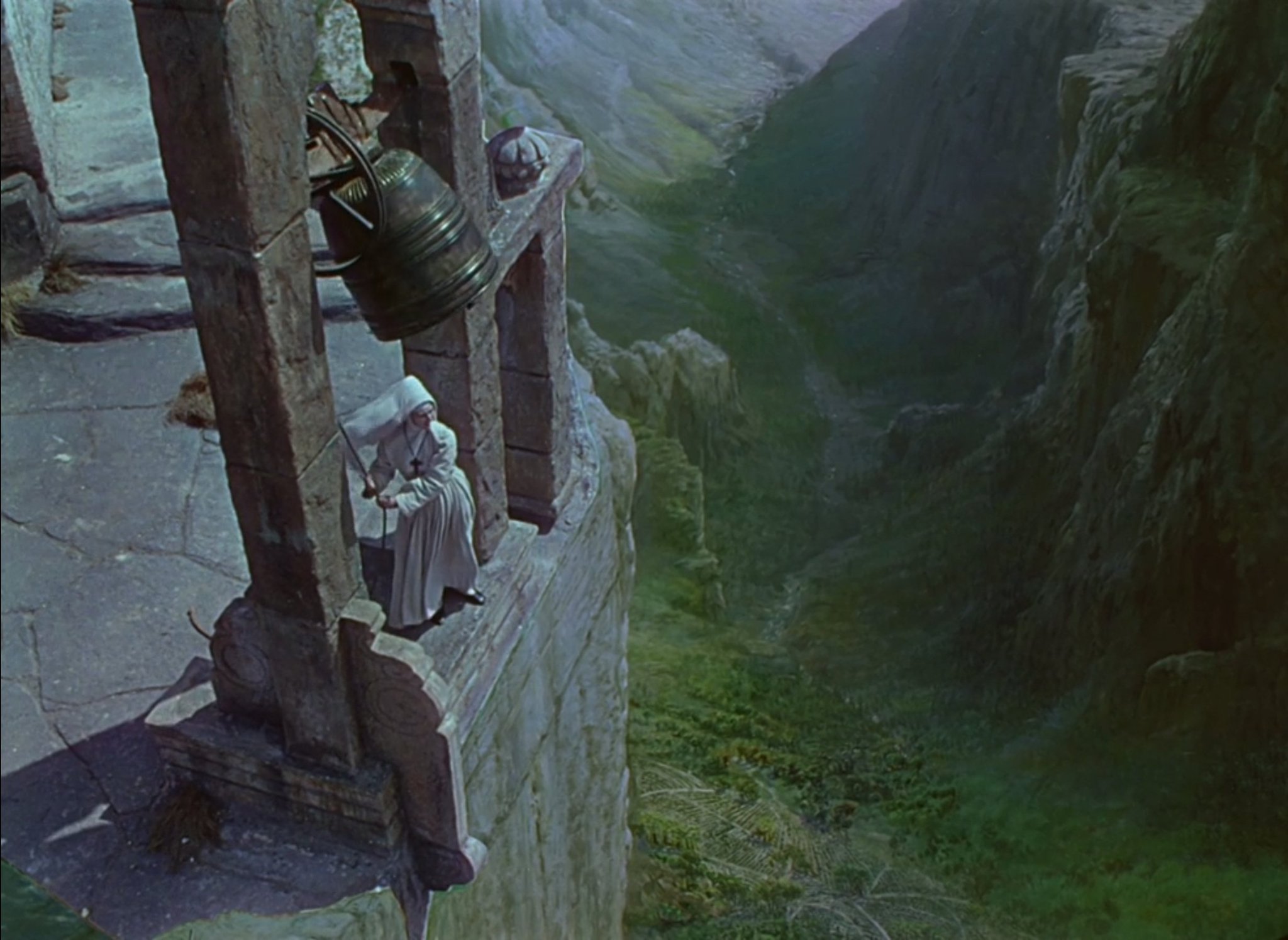

One of John Ford’s most popular films — The Quiet Man (1952) — almost didn’t happen. According to Jordan R. Young’s book John Ford’s The Quiet Man, Ford first tried to secure funding for the movie back in 1937. That was a year after he had purchased the story for just $10. Maureen O’Hara explained that it was flatly turned down by 20th Century Fox, MGM, and RKO. She said it was dismissed as a “silly little Irish story that would never ever make a penny.”

In 1946, Ford agreed to a three-film deal with Argosy Productions. If the first film made money, he would have the go-ahead to pursue his Quiet Man pet project as the third film, on the assumption that it wouldn’t be able to cover its costs. That first film was The Fugitive (1947), which as an artistic success, but a financial flop. As a result, The Quiet Man was again shelved indefinitely.

It might never have been produced, if John Wayne hadn’t approached Herbert Yates, who headed up Republic Pictures. Yates felt that television would soon chip away at Republic’s B-grade movie business. Yates also assumed that The Quiet Man wouldn’t be popular with audiences, so he insisted that Ford, Wayne, and O’Hara make a western first, so that its profits could shore up the later loss. That movie was Rio Grande (1950), which neither Ford or Wayne especially wanted to make.

As you may have guessed, The Quiet Man turned out to be highly profitable, even with its substantial $1.75 million budget. It was the 12th highest grossing film for 1952. And it was one of Ford’s personal favorites.

If you’re looking to see the film in all its glory, you’re in luck. Olive Films recently released a Blu-ray version through its Signature series that’s based on a 4K scan of the original camera negative. Originally shot in Technicolor, the disc’s colors are rich and vivid, without being overwhelming. This film won an Oscar for Best Cinematography, as well as for Best Director, and this latest restoration shows what all the fuss was about.

Extras on the Blu-ray disc include an excellent audio commentary by Ford biographer Joseph McBride, an informative 25-minute documentary hosted by Leonard Maltin, and a 12-minute appreciation of Ford by Peter Bogdanovich. Highly recommended!

The Quiet Man

(1952; directed by John Ford)

Olive Signature (Blu-ray and DVD)

Monday, March 17 at 8:00 p.m. eastern on Turner Classic Movies