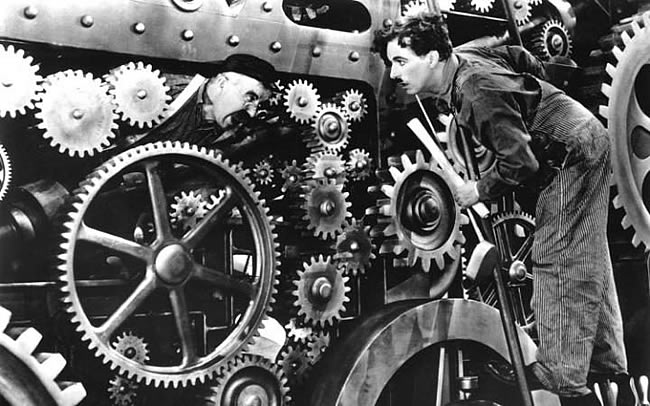

“Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long shot.”

— Attributed to Charles Chaplin

“Life is a tragedy when seen in close-up, but a comedy in long shot.”

— Attributed to Charles Chaplin

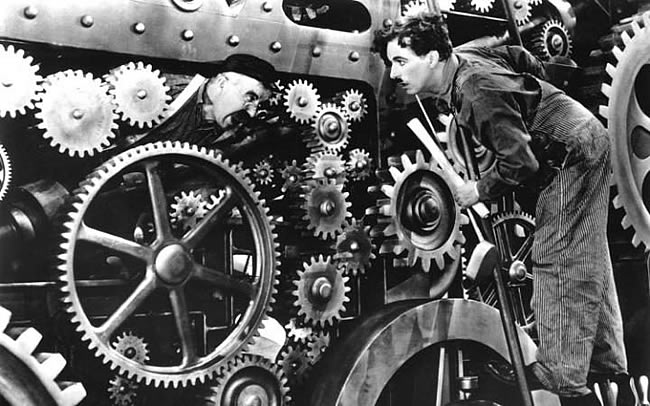

“I’ve seen Billy Wilder take suggestions from a prop man, and I don’t know a stronger director than Billy as far as being definite about what he wants, especially since he’s also the author. But he’ll listen and let you try. That’s the important thing, to at least let others try their ideas, and then say no or yes.”

— Jack Lemmon interviewed for Film Comment (May-June 1973)

“By the time we were ready to start a picture, everyone on the lot knew what we’d been talking about, so we never had anything on paper. Neither Chaplin, Lloyd, nor myself, even when we got into feature-length pictures, ever had a script. . . .

“Somebody would come up with an idea. ‘Here’s a good start,’ we’d say. We skip the middle. We never paid any attention to the middle. We immediately went to the finish. We worked on the finish and if we get a finish that we’re all satisfied with, then we’ll go back and work on the middle. For some reason, the middle always took care of itself.”

— Buster Keaton interviewed for The Parade’s Gone By (1968)

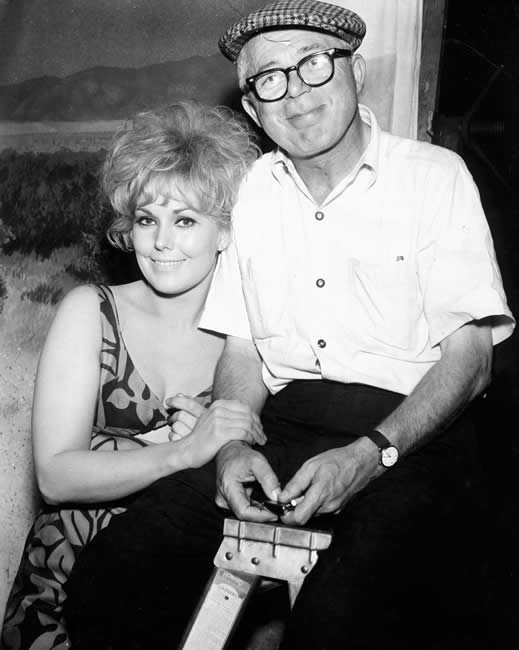

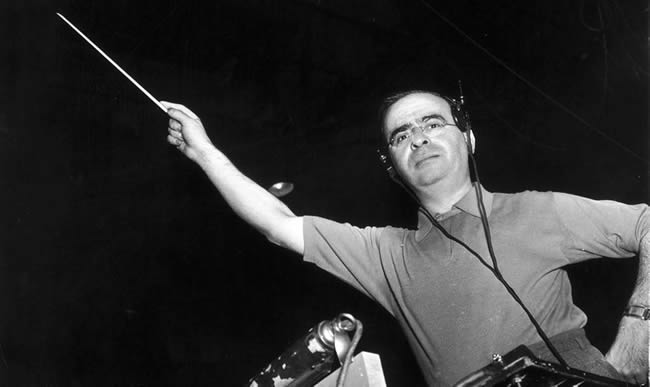

“The way I approached writing music for films was to fit the music to what I thought the dramatic story should be and score according to the way a character impressed me, whoever he might be. He may be a bastard, she may be a wonderful woman, he may be a child. I write what I see. This is very difficult for anybody to understand. Especially for anybody with such eyesight as I have. But I see a character on the screen and that is what makes me write the way I do. That is also the reason that people enjoy what they hear because it happens to fit.”

— Max Steiner interviewed for The Real Tinsel (1970)

Major T. J. “King” Kong: Survival kit contents check. In them you’ll find: one forty-five caliber automatic; two boxes of ammunition; four days’ concentrated emergency rations; one drug issue containing antibiotics, morphine, vitamin pills, pep pills, sleeping pills, tranquilizer pills; one miniature combination Russian phrase book and Bible; one hundred dollars in rubles; one hundred dollars in gold; nine packs of chewing gum; one issue of prophylactics; three lipsticks; three pair of nylon stockings. Shoot, a fella could have a pretty good weekend in Vegas with all that stuff.

— Dialogue from Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964)

Insurance Salesman: Do you know a man by the name of LaFong? Carl LaFong? Capital L, small a, Capital F, small o, small n, small g. LaFong. Carl LaFong.

Harold: No, I don’t know Carl LaFong — capital L, small a, capital F, small o, small n, small g. And if I did know Carl LaFong, I wouldn’t admit it!

— Dialogue from It’s a Gift (1934)

Jean Harrington: You know Charles?

Sir Alfred McGlennan Keith: Oh, is he the tall backwards boy always toying with toads and things? Yes, I think I have seen him skulking about.

Jean Harrington: He’s not backwards. He’s a scientist.

Sir Alfred McGlennan Keith: Oh is that what it is? I knew he was, mm… peculiar.

— Dialogue from The Lady Eve (1941)

“[For the opera scene in Citizen Kane] we needed something that would terrify the girl and put the audience a bit in suspense. I wrote the aria in a very high key which would make most performances sound strained. Then we got a very light lyric soprano and made her sing this heavy dramatic soprano part with a very heavy orchestration which created the feeling that she was in quicksand. Later on, that aria was sung many times by Eileen Farrell, who had the voice to sing it absolutely in that key, and it sounded very impressive. Some writers have said that the singer in the film performed it deliberately badly, but that’s not so. She was a good singer performing in too high a key.”

— Bernard Herrmann, interviewed for Sight & Sound magazine (Winter 1971-1972 issue)

Nora: Waiter, will you serve the nuts? I mean, will you serve the guests the nuts?

— Dialogue from The Thin Man (1934)

“Once, we were at a party in a restaurant with some twelve guests to celebrate my wife’s birthday. I hired an aristocratic-looking elderly dowager and we put her at the place of honor. Then, I ignored her completely. The guests came in, and when they saw the nice old lady sitting alone at the big table, each one asked me, ‘Who’s the old lady?’ and I answered, ‘I don’t know.’ The waiters were in on the gag, and when anyone asked them, ‘But what did she say? Didn’t anyone speak to her?’ the waiters said, ‘The lady told us that she was a guest of Mr. Hitchcock’s.’ And whenever I was asked about it, I maintained that I hadn’t the slightest idea who she was. People were becoming increasingly curious. That’s all they could think about.

“Then, when we were in the middle of our dinner, one writer suddenly banged his fist on the table and said, ‘It’s a gag!’ And while all the guests were looking at the old lady to see whether it was true, the writer turned to a young man who’d been brought along by one of the guests and said, ‘I bet you’re a gag, too!'”

— Alfred Hitchcock, interviewed in 1962 by Françoise Truffaut