The Sound of Silence

In one of the finest books ever written about comedic film, The Silent Clowns, Walter Kerr refers to Buster Keaton as the most silent of the silent film comedians:

The silence was related to another deeply rooted quality — that immobility, the sense of alert repose we have so often seen in him. Keaton could run like a jackrabbit, and, in almost every feature film, he did. He could stunt like Lloyd, as honestly and even more dangerously. His pictures are motion pictures. Yet, though there is a hurricane eternally raging about him, and though he is often fully caught up in it, Keaton’s constant drift is toward the quiet at the hurricane’s eye.

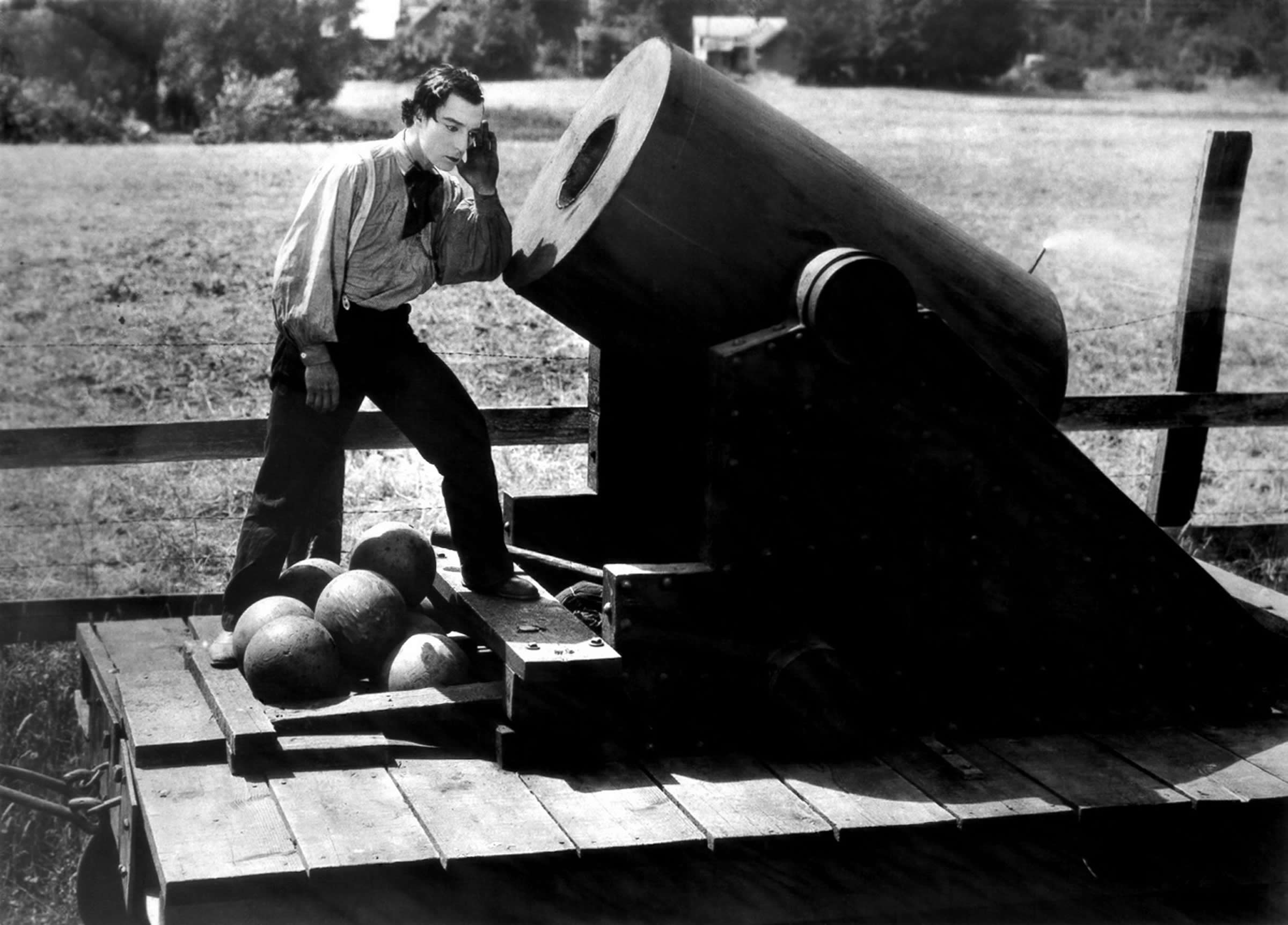

The two Keaton qualities of motion and immobility are perfectly contrasted in The General (1927). It isn’t Keaton’s funniest feature (that honor would go to Seven Chances) or his most inventive feature (that honor would go to Sherlock, Jr.). It is, however, his best blend of comedy and drama, and an ideal choice for anyone who assumes silent comedy is synonymous with empty-headed slapstick. The General has its share of laughs, gags, and pratfalls, but there’s so much more.

Here Kerr eloquently describes the climatic final scene:

As The General must be the most insistently moving picture ever made, so its climax is surely the most stunning visual event ever arranged for a film comedy, perhaps for a film of any kind. . . With all forces moving and the panorama embracing river, steep slopes, and endless forest, the train’s belly begins to droop through the burned gap in the bridge, the gap splinters wide, the understructure pulls away as the great beast seems to claw at it, and in a serpentine curve that is as beautiful as it is horrifying the train goes down to the water with its smokestack vomiting steam, a dragon breathing fire even in death. . . The awe of the moment is real: we are present in some kind of history, if only the history of four or five minutes on a day when an actual locomotive, a true burning bridge, masses of breathing men, a verifiable landscape, and a cameraman were present. Visitors to Cottage Grove, Oregon, where the shot was made, still drop by the ravine to look at the fallen locomotive; the evidence of an event remains, is still somewhat numbing.

This film has a nuanced playfulness you rarely see in comedies. One example, among many I could cite, is the famous scene when Keaton reaches out to strangle his girlfriend in frustration and then decides to kiss her instead. Is there a single moment in film or literature that better sums up the difficulty of maintaining a romantic relationship?

Another scene involves Keaton’s beloved train (The General) starting up and moving while he is sitting on the elbow-like rod that connects the engine to the wheel. Keaton is lost in thought and doesn’t realize he is moving up and down, as well as forward, until the train picks up considerable speed. We laugh because he doesn’t sense the movement right away. We also laugh (or should laugh) because this gag works strictly in a silent medium. In the real world (or in a sound film), we would wonder why he didn’t hear the engine. The in-joke for Keaton and his 1927 audience is that this is a jab at silent film conventions. If you think I’m stretching the point, you only have watch Sherlock, Jr. (1924) to see Keaton poke fun more openly at film logic and the very vocabulary of filmmaking. That’s the wonder of Keaton’s genius — his movies are satisfying on so many different levels.

The General

(1927; directed by Clyde Bruckman and Buster Keaton)

Kino Video (Blu-ray and DVD)

Tuesday, March 11 at 3:30 p.m. eastern on Turner Classic Movies

Reviews