A great film depends on everything coming together into an unlikely alignment. If a director, actor, screenwriter, cinematographer, composer, or other essential component is lacking, you may end up with only an interesting film that shows promise.

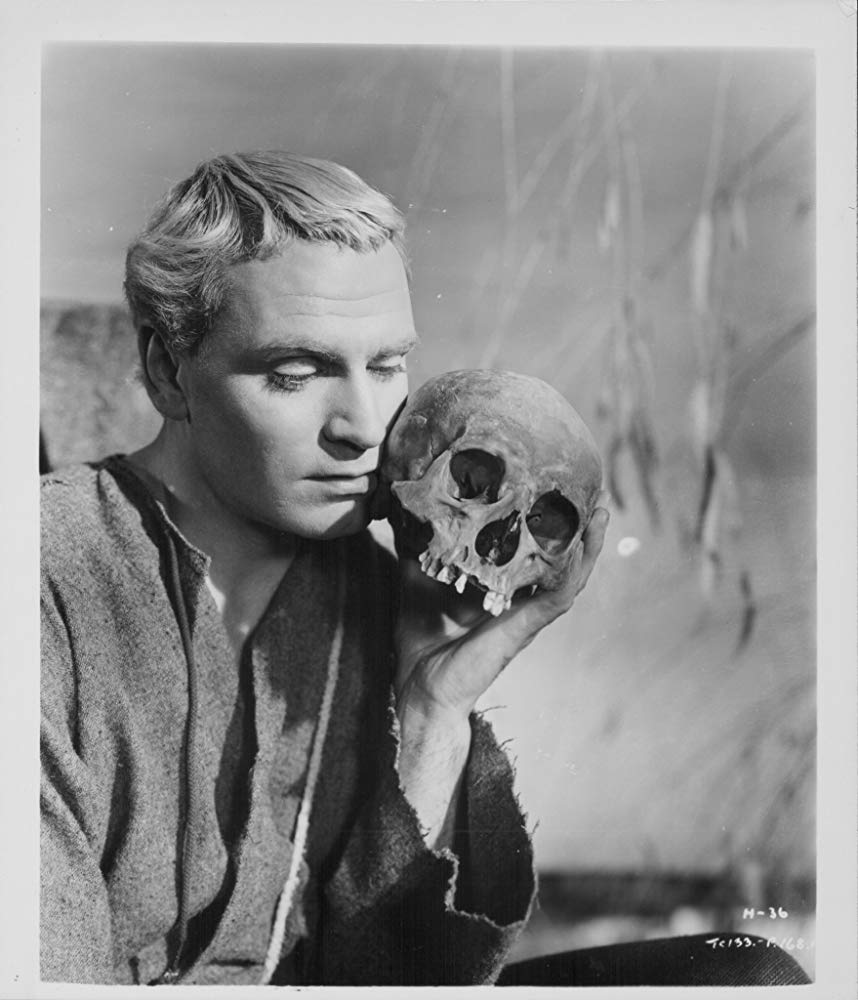

With The Red Shoes (1948), so many things that could have gone wrong, didn’t. Michael Powell could have chosen to use actors who could dance, rather than dancers who could act. His strategy was high risk, but promised to pay off big — if he could find the right dancers. Basing the story on a dark fairy tale from Hans Christian Anderson was equally perilous, unless Emeric Pressburger’s script could successfully emphasize the warmth and humanity of the ballet company, as much as their artistic spirit and integrity of purpose. And inserting a 17-minute ballet sequence, not at the end of the movie as an emotional climax, but near the middle to place the emotional conflicts into stark relief, would have been commercially foolish if not handled skillfully. That all these things succeeded so spectacularly, when any one of them could easily have failed, is a credit to those involved, but also a fortunate happenstance that all the participants agreed to come onboard.

Much of the audience’s empathy is dependent on the acting talent of Moira Shearer, who was just 21 years old at the time. A dancer at Sadler’s Wells (later renamed the Royal Ballet), Shearer wasn’t eager to put her dancing career on hold, as she explains in this 1994 interview with Brian McFarlane for An Autobiography of British Cinema:

I held out against that film for a whole year. The director Michael Powell was extremely put out by my continued refusal. It never occurred to him that a young girl wouldn’t be overwhelmed by his offer. But I didn’t like the story or the script, which seemed a typical woman’s magazine view of the theatre, and I also realized he knew very little about the ballet. Also, at that time, 1946, I had just started to dance the ballerina roles in the big classics and the last thing I wanted to do ‘was to interrupt this difficult work with a sugary movie.’ Powell bombarded me for weeks in 1946 and I remember thinking, ‘I have to get rid of this man.’ However, he finally got the message and went off in a huff, saying to me, ‘I am now going around the world to find the perfect girl for this part.’ He came back a year later; presumably he hadn’t found his perfect girl, though he had now engaged Leonide Massine and Robert Helpmann, both of whom I knew well, as dancer-actors and to arrange the choreography. Powell went on and on at me and I think he must have bombarded Ninette de Valois because she called me to her office and amazed me by saying, ‘For God’s sake, child, do this film and get it off your chest — and ours, because I can’t stand that man bothering us any longer!’ I asked one question, ‘If I do it, can I come straight back to Covent Garden when the film is complete?’ and her answer was, ‘Yes, of course you can.’ And I did — but not happily. There was a lot of jealousy and bad feeling. I’m afraid I was very naive. Helpmann told me later that the only reason de Valois wanted me to make the film was to give advance publicity in America for the first coast-to-coast tour of her company in 1949. Which, of course, is what happened.

Jack Cardiff also wasn’t eager to join the project. He had worked as the cinematographer for Powell on A Matter of Life and Death (1946) and Black Narcissus (1947), but wasn’t enthralled with the idea of photographing a movie about a ballet company. Powell asked Cardiff to regularly attend the ballet at Covent Garden, where he saw the possibilities of what he could bring to the film. One example was a special camera Cardiff designed that let him vary the film speed while the dancers performed. By slowing down their movements imperceptivity, he enhanced the visual impression they were soaring through the air or reaching extreme heights. Cardiff was probably the finest Technicolor cinematographer ever, and two of his films — Black Narcissus and The Red Shoes — are often cited as the best examples of what can be achieved with the Technicolor process.

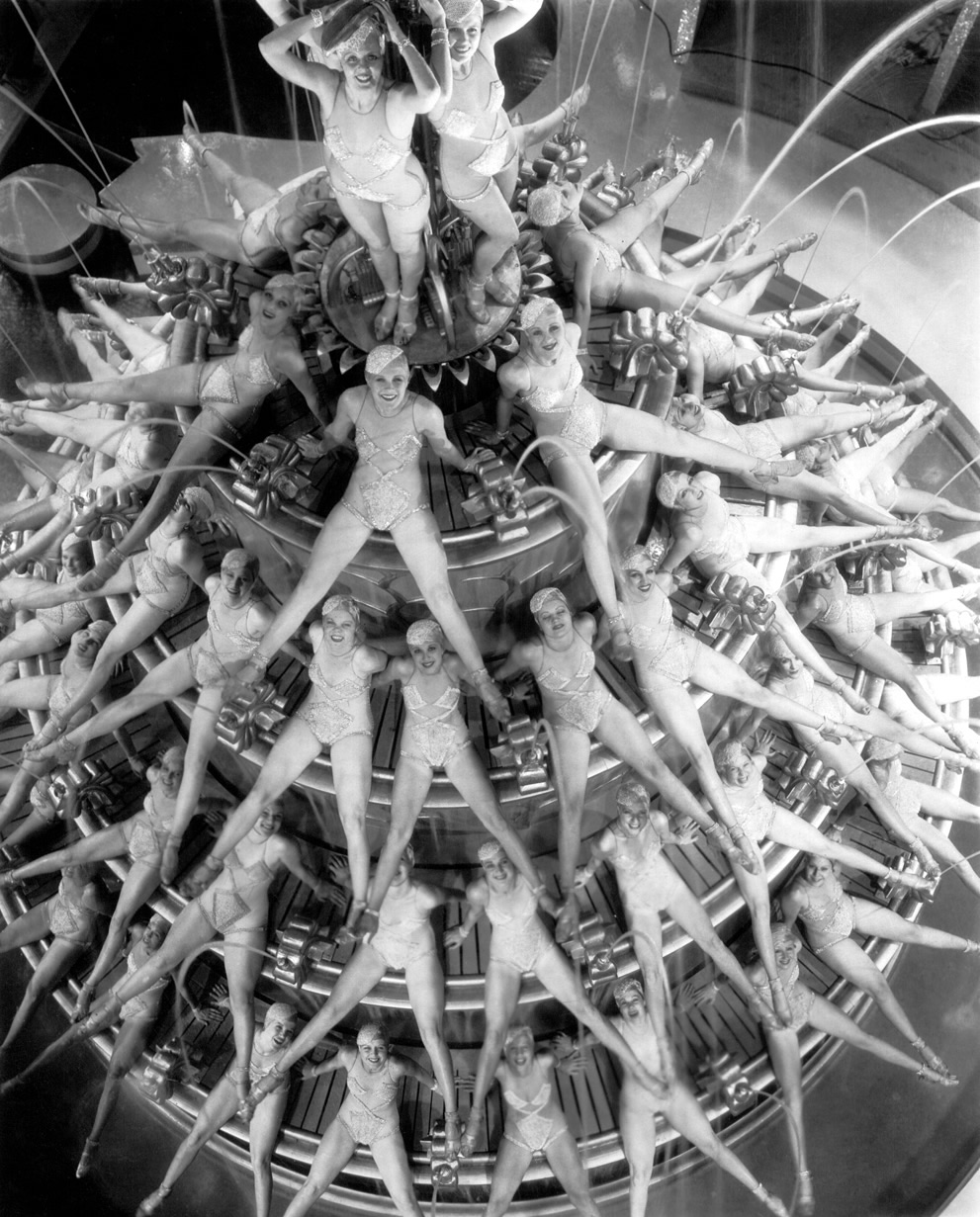

Though risky, The Red Shoes was a financial success. In the U.S., it began quietly with a 110-week run at The Bijou in New York City and was then picked up for national distribution. It had a strong influence on Hollywood musicals. The extended ballet-like sequences in An American in Paris (1951) and Singin’ in the Rain (1952) might never have been approved without proof there was an eager audience for this merging of art forms.

The Red Shoes

(1948; directed by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger)

The Criterion Collection (Blu-ray and DVD)

Sunday, January 12 at 11:45 a.m. eastern on Turner Classic Movies